VIdeo game console manufacturers, set-top box makers, and even television manufacturers are all clawing to get their hands on a partnership with Netflix or Blockbuster Online so buyers can do what they obviously want to do; stream audio and video straight to their HDTVs.

The rationale is simple – streaming Netflix and Blockbuster Online over broadband to the home has become a huge part of both companies’ business models, and clearly video on demand is the future of rented movies and material. Even Netflix’s CEO said that they expect their physical disc-mailing business to decline over the next several years as their streaming business soars.

So clearly the general public is happier with paying for temporary access to video content, whether they pay Netflix or Blockbuster Online to send them DVD or Blu-Ray discs straight to their homes, where they watch them and then return them in a mailer or they get the content streamed directly to their XBox 360 or their Boxee Box or their HTPC. We’re all comfortable with the concept that we pay a monthly fee to watch as many movies as we can stand or the mail can deliver to us, and when we’re finished watching or we send it back, the movie’s gone forever unless we want to watch it again. When we cancel our accounts with Netflix or Blockbuster Online, our access to that content is gone forever.

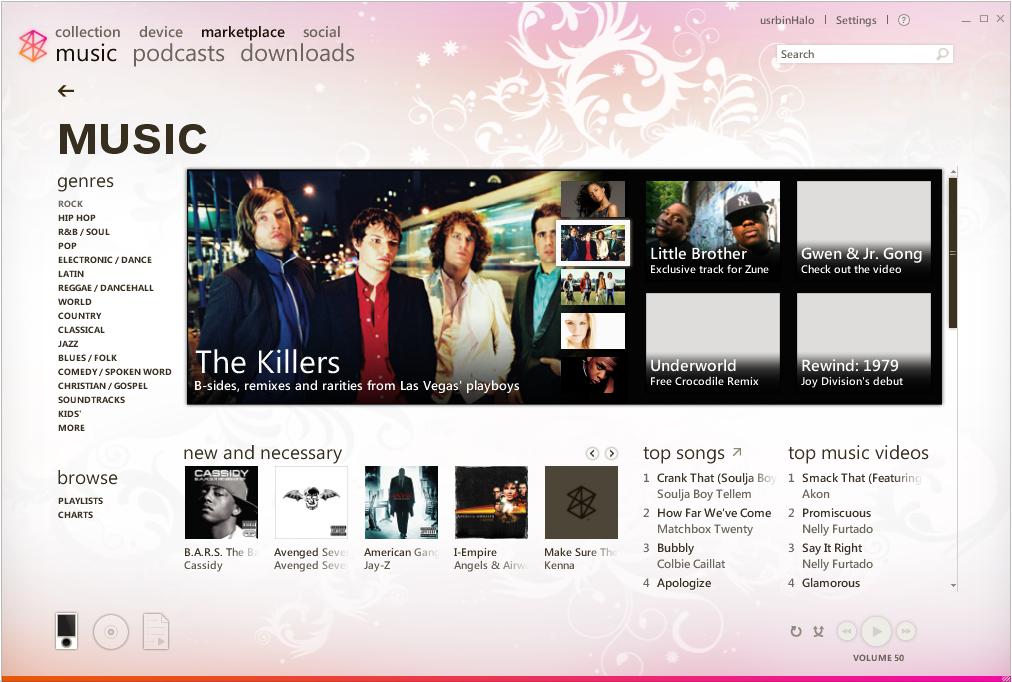

So, then, why isn’t the same for subscription music services? The Zune Marketplace, Rhapsody, Napster, all of those services operate using exactly the same business model, if not more generous than the video services’ are. The Zune Marketplace, for example, gives you a number of credits you can spend monthly to download and permanently own the songs you really like, instead of losing access to them if you ever terminate your account. Netflix doesn’t say every month “you’ve been such a great customer, why don’t you keep these movies from your queue, go ahead, take them,” but in order for a service like the Zune Marketplace to survive, they have to.

Why are we so okay with essentially leasing our movies from Netflix and Blockbuster Online, but we’re not okay with leasing our music from Zune Marketplace and Rhapsody in the exact same way? I have a couple of ideas, but it mostly has to do with history and perception – not functionality. Let’s dive in.

This isn’t entirely a defense of subscription music services, although I admit that I have a hard time discounting them as much as I used to now that I realize how hypocritical it can be to love subscription video services for one reason and then hating subscription music services for the same reason. It’s difficult to maintain that the iTunes model, for example, that lets you own your own music once you’ve purchased it, is so much leaps and bounds ahead of its major competitor, the Zune Marketplace, when you realize that Netflix doesn’t let you “own” your own movies any more than the Zune Marketplace lets you own your music – in fact, the Zune Marketplace is much more lenient, and gives you the ability to download songs to keep yourself forever even if you cancel your Zune Marketplace subscription.

So what’s the major difference? Why does the thought of “rented music,” a la subscription music services, raise people’s hackles and bring to mind the rabid “information wants to be free” rhetoric where services like Netflix, which makes its money renting you movies, doesn’t? Do we fundamentally view video and audio as qualitatively different?

The answer is no, not really, but there are some things that make us more protective of our music than we traditionally have been about our movies:

The Spectre of DRM

Subscription music services still reek of DRM, and this is probably the biggest thing that’s turned people off about them. There are naturally built-in protections to make sure that the music you have on your computer or your mobile device by virtue of your subscription to the service can only be played as long as your subscription is valid – that part isn’t really under dispute. What does become a problem is the historical precedent that subscription services saddle you with only a handful of supported players, and usually not very good ones that people actually want to buy.

This rings like the iTunes/iPod circular relationship, which also chafes a number of people (but given the massive popularity of the iPod as a music device Apple has been able to get away with it) but the combination of not really being able to play your music on any device AND the stigma that came with not totally “owning” your music was too much for a lot of people to bear. Assuming that using Napster required that you use a pretty poorly rated Samsung mp3 player and on top of that you could only play or share your music the way you were told was just a huge turnoff for a lot of people.

This is where one of the parallels between subscription services for audio and video break down. The parallel to this would be if in order to use Netflix you HAD to use a certain device to play the video on your HDTV – one sanctioned by Netflix, and if you tried to use something else it just wouldn’t work, including with your mailed discs. You could see how this would be a problem for people.

Thankfully, with the launch of Amazon MP3 and the change of heart that Amazon and Apple took towards DRM, the fall of DRM opened the door to a much more trusting relationship between subscription service providers and their customers. For example, with the Zune Marketplace, the songs you get to keep are in mp3 format, and the songs you “rent” are in protected WMA, which means any player that can play WMA can play the files – it’s just that when your subscription is cancelled, they’re removed from your computer.

The spectre of DRM is largely gone from subscription music services, and only remains as a way to validate that you’re an active subscriber. The demons of Microsoft’s PlaysForSure debacle and Sony BMG’s rootkit fiasco all still ring in music consumer’s minds as a reason to stay away from any service that doesn’t affordably allow you to download and completely own, free and clear, the music that you purchase.

It’s understandable, but subscription services have adapted and grown since those days, and they’re worth another look. A number of them allow you to subscribe and stream music just like music discovery services like Last.fm or Pandora, and spin the subscription as a way to get customized radio of music you would like based on songs you already own or songs you rate highly. Then you have the ability to buy stand-alone downloads that belong to you in DRM-free mp3 format. The Zune Marketplace is a good example of a service which started out pretty poorly and came a long long way – it’s music discovery engine surpasses Apple’s Genius in a number of ways, and can generate playlists based on songs you own or songs you find in the catalog using songs you own or songs in the catalog that you can rent or buy.

The flip side to this is video on demand services like Netflix and Blockbuster Online, which ship you discs that you can keep as long as you want as long as you’re a subscriber. If you ever cancel your subscription, you have to send the discs back or pay to own them. Video streamed over the Web to your HDTV or console is only available to you for a short time, cached on your device. When it’s gone, it’s gone forever – you have no option to own it, and neither service currently allows you to even pay to download the movies you stream permanently. (although it’s likely coming.)

In some ways, subscription video is less flexible in this regard than subscription audio – it’s just that the spectre of DRM isn’t necessarily applied: there’s no “you kinda own it while you pay us” aside from having a physical DVD. In this case, it’s probably more history, media, and the echo chamber that makes us more afraid to keep protected WMA on our computers to listen to whenever we want for the life of our Rhapsody subscription than we are unhappy that the instant we turn off our XBox 360, we lose the Netflix movie we were watching back to the ether, never to become part of our collection.

Collector’s Mentality

While I think DRM and the horrible history of the music industry treating its consumers like criminals is the real reason why people want complete and utter control over their music (and subsequently, the MPAA being somewhat careful about demonizing itself to its customers and trying to learn from the mistakes of the RIAA – even though they’ve only been partially successful, seriously the “You wouldn’t download a car” campaign is laughable) and willing to be a bit more lenient about the degree to which they own their movies.

At the same time, I think people have a different perception of what it means to have a music collection and what it means to have a movie collection. Movie collections and owning movies digitally simply haven’t gotten to the point where the majority of people are comfortable with their movies on a hard drive or a computer or another device hooked up to their television. When the average American wants to watch a movie, they expect to look at a shelf and pick something they’d like to watch, and physically put a disc in a player.

Granted, all of this is changing with streaming video to your set-top via game console, widget-powered TVs, and Blu-Ray players with network connectivity, but it’s just not at critical mass yet. Just like with the compact disc, the tide has only now begun to shift in the direction of people understanding that owning their media in some digital format on a box that’s near the TV is okay – and in some ways preferable to – having lots of boxes and disc cases on a shelf next to or under the TV. I also get the feeling that people will be more clingy to physical video media for longer than they were for the CD, especially with the advent of Blu-Ray. (which give your more features and greater video quality than you can get by streaming the same video via broadband – although that’s changing too)

The tide is changing in people’s perceptions of what it means to have a “movie collection,” and it’s shifting to set-top boxes and HTPCs the same way as people understand now that having a “music collection” doesn’t necessarily mean bookshelves of CDs and can instead mean a couple of external hard drives or a single iPod on a desk. The trick is that it’s just not there yet.

Wrapup

In the end, don’t really mean to claim that there’s a definitive or correct reason why people trust rented video, both on demand and physical, when they don’t trust rented audio in the same shape and fashion – even from companies whose business models line up very very closely. There are likely more reasons than these to explain the phenomenon, but unfortunately, some really grreat subscription music services have gone under the radar partially because of this negative stigma applied to them and partially because there are just so many great music discovery and download services that let you buy music free and clear.

Add to this the “us versus them” stigma that’s applied to just about every product or company, and you have people who won’t look twice at Zune Marketplace because they hate Microsoft, for example, or people who won’t touch Rhapsody because it’s from Real Networks, or worse, people who won’t consider them because they already use iTunes or Amazon MP3 and dare not use more than one service for their music, as if it’s “cheating” somehow.

Being an music lover, I can see the benefit of a subscription service that lets you snag and listen to as much music as you can possibly stand for as long as you can stand to pay the monthly fee while also direct downloading the tunes you know you’ll love forever or have some special meaning to you. (or want to use to complete you collection or an artist’s discography!) I feel the same way about movies as well – I’m a very happy Netflix subscriber and think that streaming video direct to my HDTV is a fantastic thing, but I wouldn’t sacrifice my shelf of DVDs for the world, and I’ll definitely buy Blu-Ray videos in additon to using Netflix for other videos I’m comfortable renting.

Explore multiple options, and try different services. You might surprise yourself.

The way we consume these media is different, too. I notice you didn’t really get into ownership/rental of digital books: That’s visual content without the audio, to complete the media types you mention. (Audio only and audio with visual.)

Music you can consume on your way between things without too much loss of concentration.

Movies you can consume in the background and often as the primary focus of your attention.

Digital book consumption is a destination activity. You can’t do it in the background.

Does that factor in? Maybe. I don’t really know, but I’d like to hear what you think.

Bandwith is still a problem.

It’s true – bandwidth is still a problem. And while a lot of improvement has been made in data compression, it’s difficult when you have ISPs with bandwidth caps.

You’re right though – ebooks aren’t really my thing, so I don’t know enough about them to really speak to them: I do, however, know a lot of people who refuse to invest in an ebook reader or in ebooks until they can sell or trade used ones.