(this brand new image for Spinning Gears columns is courtesy of Narilka, who graciously gave permission to use it!)

I covered this story over at AppScout today, but I think not only does it bear repeating, but it just sparks some interesting thinking about the way the Web works and who’s really a customer of whom on the Web these days. It’s surprising how many common URL suffixes are actually owned by foreign powers who may or may not have their customer’s best interests at heart – and certainly may not have the same passion for free and open speech on the Internet as those companies – especially if they’re American or European – may have.

Here’s a lift from my story, for those folks who don’t want to click the link:

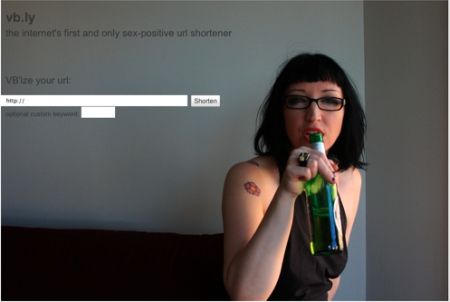

For example, co-founders of the vb.ly URL shortening service Ben Metcalfe and Violet Blue both posted warnings today that the vb.ly domain had been seized by the Libyan government for first being in violation of their terms of service agreement, but was later clarified to mean that the content of the vb.ly site, which featured Violet Blue herself holding a green glass bottle while wearing a sleeveless blouse, violated Libyan Sharia law.

Additionally, the Libyan officials that Metcalfe and Blue contacted about the issue responded that .ly domains shorter than four characters were now to be reserved for use by Libyan businesses and organizations.

Worth referencing, as I did in the story, is Brian Metcalfe’s post at his blog and Violet Blue’s post at TechYum about the incident, complete with records and exchanges from Libyan officials about the matter.

The critical thing to note here is that Libya is the owner of every domain that ends in “.ly,” and when you register and purchase a .ly domain you’re not so much getting ownership as you are signing an agreement to use the domain with the cooperation of the Libyan government, and their domain registration authority, NIC.ly. So that means services that are commonly used by lots of people (myself included) like the bit.ly URL shortener, the ow.ly URL shortener, and the ad.ly advertising URL shortener, are all subject to the whims of the Libyan government for their terms of service agreements.

Now, not to paint the Libyans in too bad a light here: the country is a Muslim country and they’re guided by Islamic/Sharia Law – meaning that a free and open internet for all subject matter isn’t exactly one of their core principles, and is pornography and adult content is expressly forbidden by their morality code. When they learned who Violet Blue – co-founder of the vb.ly URL shortener – was and likely did a little research, they jumped to shut the shortener down, regardless of the fact that the vb.ly page is anything but unsafe-for-work (shown above before it came down) and the content of the URLs shortened by the service were likely in part adult material but certainly weren’t exclusively adult material – no more so than ow.ly or bit.ly, I’m sure.

It’s not the adherence to Sharia Law that bothers me here, it’s the fact that the Libyan government has stated that they want all sub-four character .ly domains to be reserved for use by Libyan businesses and local organizations. That in itself doesn’t bother me, but it’s the application of both of these rules that’s the irritant, and that has such huge consequences for the rest of the Web – Libya’s information officials are essentially using Sharia Law as a scapegoat and a convenient excuse to shut down vb.ly, and are immediately reclaiming it in line with this new “locals only” policy. Essentially, two very weak excuses for action that’s far more aggressive than is warranted.

If Libya wants to reserve URLs for internal use, that’s their business – they own the .ly suffix. If they want content that passes through .ly suffixed domains to be compliant with Sharia Law, that’s also their business. The problem is when they strong-arm their want into a battle over values, freedoms, and speech on the Internet by bullying businesses and other parties instead of simply making their case and asking for a change.

If Libya had said they weren’t going to renew the registration to Ben Metcalfe and Violet Blue when it came up because of these two policies and rules, I doubt there would have ever been this controversy. As it stands however, it means that every company that deals with a foriegn power for its domain suffix – especially those using .ly – stand at risk to be shut down immediately and without notice should they enter the crosshairs of that nation’s government officials.

I don’t have a problem with national governments dictating and changing the terms of the use of their domain suffixes.

Are you asking that they’d be beholden to a higher authority? That the IANA enforce that domains be for sale to foreign entities because the combination of letters holds some meaning in the foreigner’s language?

Why are any of the .ly domains *not* about Libya, anyway? Because it’s short? Because it makes a cute name in a foreign language?

Are you still disappointed that del.icio.us redirects to delicious.com? Do you expect doof.us to be about the government of the United States of America?

Let me be clear: like I said in the post, I don’t have a problem with the Libyan government’s decision to reserve .ly addresses for local interests, and I don’t even object to their decision to shut down vb.ly because of their interpretation of Sharia Law.

I took issue with HOW they did it, not WHAT they did.

I have no particular interest in making all of the nations of the world surrender control of their ccTLDs to someone like the IANA unless they decide to do so – I’m all for a free and open Internet, but I’m also all for the rule of law, and that varies from place to place.

I also have no interest in requiring those ccTLD domsains to be sold to anyone in particular or be about anything in particular. The governments of Tuvalu (.tv), Columbia (.co), and Libya (.ly) enter voluntarily into business arrangements with companies outside of their borders that show interest in paying them for their TLDs – they can do so freely if they choose, and they can not do so if they choose.

I’m not certain if I came off anywhere in my post that any of the issues you brought up were of note to me – they’re really not.

My concern is with the chilling effect that comes with arbitrary action by anyone outside of the scope of an agreement. If Libya wants bit.ly for themselves, they should be free to take it for their own use….according to the terms of the contract and agreement they entered into with good faith.

If they wanted vb.ly, I feel the same way – they’re welcome to it – there’s just no reason to hide behind Sharia Law (something that NIC.ly knew would enflame the sensibilities of people who know little of Sharia Law) or the so-called pornography argument. I think both of those are irrelevant.

Next time they’ll make a point of hiding behind Eminent Domain when they take away the subdomains, then.

I kid, I kid.

Yes, it does suck. I was just trollishly taking the side of: “You had to know it could happen. It could happen with .us domains, too. That’s the risk you take when when you choose a cutesy domain name that has NOTHING TO DO with the country it belongs to.”